Richard Trevithick, (image shown opposite), deserves a place alongside the other pioneers of steam engine developments like Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. He is credited with inventing the first high-pressured steam engine and the first operational steam locomotive (1803). He was born in Carn Brea in Cornwall which was at the centre of the then thriving mining industry in the county. His father was a mine captain and whilst attending Camborne School Richard became fascinated by the industry. In 1786 there were 21 Boulton and Watt steam engines operating in Cornwall and he learnt how they were designed and worked. He was a very confident and enthusiastic individual and because of his height became known as the Cornish giant. He started work at the age of 19 at the East Stray mine near Camborne under the supervision of William Bull who manufactured steam engines which were different from Watts’. In order to avoid the inventor’s patent Boulton and Watt sued Bull over violation of the patent and Richard Trevithick appeared as an expert witness in opposition to Watt which increased the hostility between Trevithick and Watt.

Richard Trevithick, (image shown opposite), deserves a place alongside the other pioneers of steam engine developments like Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. He is credited with inventing the first high-pressured steam engine and the first operational steam locomotive (1803). He was born in Carn Brea in Cornwall which was at the centre of the then thriving mining industry in the county. His father was a mine captain and whilst attending Camborne School Richard became fascinated by the industry. In 1786 there were 21 Boulton and Watt steam engines operating in Cornwall and he learnt how they were designed and worked. He was a very confident and enthusiastic individual and because of his height became known as the Cornish giant. He started work at the age of 19 at the East Stray mine near Camborne under the supervision of William Bull who manufactured steam engines which were different from Watts’. In order to avoid the inventor’s patent Boulton and Watt sued Bull over violation of the patent and Richard Trevithick appeared as an expert witness in opposition to Watt which increased the hostility between Trevithick and Watt.

During the late 18th century many engineers were trying to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of steam engines. Watt was very sceptical stating that they ‘were all on the wrong track’. Trevithick struggled financially but was supported by his cousin Andrew Vivian and gained a great deal of scientific guidance from Davies Gilbert the MP for Penzance and Bodmin. Gilbert offered advice of how the steam pressures could be best operated in regard to the pistons and the cylinders. Gilbert went on to be elected president of the Royal Society succeeding Humphry Davy – note again the Cornish connections.

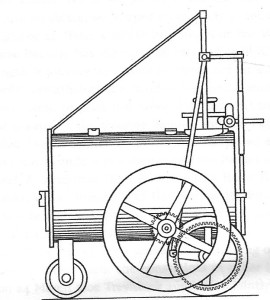

In 1796 Trevithick constructed two steam engines, one to drive a locomotive, the second a free standing/static engine. These were much simpler than the Boulton and Watt engines and delivered greater levels of power. He further developed these engines to drive winding wheels at Wheal Hope mine and quickly realised their potential because of their relatively small size, lightness and power capability to drive vehicles. On 24th December 1801 he drove a single-cylinder steam engine called the ‘the Puffing Billy’ in Camborne for a distance of one kilometre. In-spite of the short distance the event proved a great success which heralded a new age of faster travel. Initially the distance travelled was limited by the great consumption of water but further improvements with his partner Vivian overcame this and other problems. A picture of ‘the Puffing Billy’ is shown below.

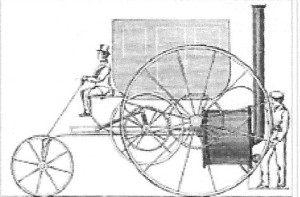

In 1803 he decided to demonstrate his steam carriage in London when trials were staged at Lord’s cricket ground and then down New road and Gray’s Inn Lane. However these ambitious demonstrations had limited success which caused some of his financial supporters to doubt the engines true potential. Four fatalities occurred when one of his pumping engines exploded and this caused further reservations prompted by Boulton and Watt’s heavy criticism of Trevithick and his inventions – such was their hostility to him! A picture of the London Steam Carriage locomotive by Trevithick and Vivian that was demonstrated in 1803 is shown below.

However again help was on hand when Samuel Homfray owner of the Pen-y-darren ironworks in Wales bought the rights to some of the patents. In 1804 a new more powerful engine was used to win Samuel Homfrays bet that the engine could pull ten tons of iron along ten miles of tramway. This and other successes allowed Trevithick to continue his work on improving the steam engines both static and for locomotion. These steam locomotives would ultimately transform steam engines and allow a faster and safer mode of travel. In addition he developed a wide range of static steam engines used in boring, crushing, dredger (1806), iron rolling and milling (1805), pumping, threshing machine (1812) etc. He also developed a marine engine to drive paddle steamers as well as telescopic masts, buoy and floating docks.

However again help was on hand when Samuel Homfray owner of the Pen-y-darren ironworks in Wales bought the rights to some of the patents. In 1804 a new more powerful engine was used to win Samuel Homfrays bet that the engine could pull ten tons of iron along ten miles of tramway. This and other successes allowed Trevithick to continue his work on improving the steam engines both static and for locomotion. These steam locomotives would ultimately transform steam engines and allow a faster and safer mode of travel. In addition he developed a wide range of static steam engines used in boring, crushing, dredger (1806), iron rolling and milling (1805), pumping, threshing machine (1812) etc. He also developed a marine engine to drive paddle steamers as well as telescopic masts, buoy and floating docks.

Successful as he was with his inventions he possessed poor business sense and financial skills and experienced a number of bankruptcies. Three years after bankruptcy in 1811 an order for his engines was made by a silver mine in Peru and he decided in 1816 to seek his future and fortune in South America. In South America he again showed his extraordinary ability and enthusiasm being prepared to throw himself into all sorts of challenges and projects. He was appointed as an engineer in Lima but then the war of independence broke out. He served in Simon Bolivar’s army and then travelled extensively in Colombia, Costa Rica and Ecuador hoping to develop mining machinery and identify routes to transport ore and equipment but the independence wars that were sweeping the continent greatly curtailed his ambitions and he returned to England in 1827 penniless only to find other engineers had profited from his inventions including George Stephenson. George Stephenson however recognised Trevithick’s achievements and petitioned Parliament to give him a pension but this request was refused – another example of the commitment by politicians’ to technical and industrial development! He died in poverty in Dartford on 22nd April 1833 and buried in an unmarked grave.

A truly remarkable individual who has not received the recognition he deserves. Having lived and worked near Carn Brea and Camborne in Cornwall I know how much he is revered.

There is a Richard Trevithick Society which publishes newsletters and journals on him and the mining industry.

References:

Burton. A. ‘Richard Trevithick: Giant of Steam ISBN 1-85410-878-6. London. Aurum Press. 2000.

Dickinson. H. W. and Titley. A. ‘Richard Trevithick.’ CUP. 1934.

Dickinson. H. W. and Titley. A. A Short History of the Steam Engine.’ CUP. 1938.

Osborne. R. ‘Iron, Steam and Money: The Making of the Industrial Revolution.’ Pimlico. 2014

Recent Comments